In 2006, Google Translate appeared on the internet. In 2007, I graduated from university where I had studied translation. As you can imagine, I’ve been hearing for years that Google Translate will make my job obsolete, that machines will soon do a much better job than me and for hardly any money at all – and that I should probably find a new area to work in while I still can. But how accurate is Google Translate really? Let’s look at this more closely and find out if machine translation will make my job obsolete anytime soon.

What is machine translation?

Machine translation is a clever invention. Dictionaries tell people the German word for any English word you can think of. Languages have grammar rules. If you give a computer a dictionary and grammar rules, it should therefore be able to turn English sentences into German sentences. That’s essentially what machine translation is.

Technology advances very quickly, of course, and nowadays we have things called artificial neural networks and they do fancy things like neural machine translation (NMT). An artificial neural network is a “a framework for many different machine learning algorithms to work together and process complex data inputs” (says Wikipedia). In practice you could feed 1000 photos to a computer and mark every photo that has a giraffe on it. Through the magic that is deep learning, the computer could then go ahead and decide for every additional photo you provide whether or not it has a giraffe on it.

If you’re into photography and you’ve used Adobe Lightroom before, you might be familiar with this technology. Adobe Lightroom can “guess” who is shown on any given photograph once you have started labeling your photos. This is a good opportunity to show you the limitations of neural networks. Apparently, it’s determined the carpet looks like me.

What is human parity?

Parity is another way of saying equality, so when people talk of human parity in the context of machine translations, what they mean is that the quality of the machine translation is equal to what a human would produce.

In a talk for the Globalization & Localization Association titled “Human Parity in Automatic Translation. How Far Are We?”, Chris Wendt of Microsoft talked about Microsoft’s claim of having reached human parity for translating a (linguistically) distant language pair – Chinese and English. He went on to define human parity as follows: “If there is no statistically significant difference between human quality scores for a test set of candidate translations from a machine translation system and the scores for the corresponding human translations then the machine has achieved human parity.” Then he went on to explain that they were not comparing their results to those of subject-matter experts, but to crowd-sourced translations, post-edited machine translations and the translations done by translators who were not subject-matter experts. No doubt about it, what they have achieved is still no small feat. But it is also not as impressive as it first sounded.

Still, advances in technology are astounding. In one of my classes at university (so before 2007), we were tasked with calling a number of the German railway company (Deutsche Bahn) and getting info from them. They had implemented a system that was supposed to understand what you were saying and provide you with an answer. It would ask something like: “Where do you want to start your journey?” and you’d say: “Hamburg.” Then it would ask: “What’s your destination?” and you would reply: “Berlin”. Then it asked when you wanted to travel and eventually let you know that your train would leave at 11:30am. It worked if you spoke clearly, but it was a rather slow process (they charged you by the minute for it) – and it was far away from today’s Google, Siri or Alexa.

But what do those services do, really? They turn sound waves into text and use the text to provide answers – presumably by sticking it into a search engine and reading the results. So Google’s, Siri’s and Alexa’s scope is fairly limited – even if what they can do is very impressive. Let me go out on a limb here and claim that it’s a lot easier to turn sound waves into written text than it is to take text in one language and render it in another.

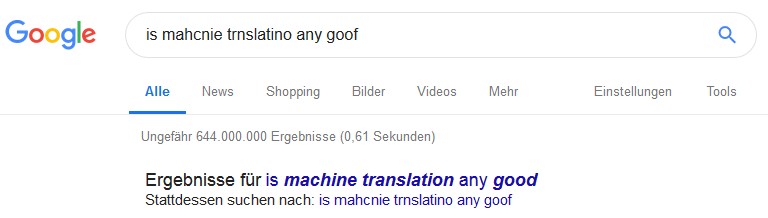

How accurate is machine translation?

The accuracy of machine translation depends on the text and languages you are translating. It can produce good results for simple text in related languages and do very badly for complicated text in unrelated languages. Three questions are relevant here: What are you translating? Which languages are you translating? And what are you translating for?

What are you translating?

There’s a practice called writing for machine translation, which simply means that you create text that is simple enough so a machine can translate it. This includes writing short, simple sentences in the active voice, not using culturally specific information, humor, slogans, anything that could be ambiguous. Also, repeat your nouns as often as possible, rather than using the pronoun “it”. (See more tips for writing for machine translation on the IBM Cloud.) If you stick to these rules, machine translation might work out quite well for you. As with Siri or Alexa, this is the small scope in which machine translation actually fares quite well.

Which languages are you translating?

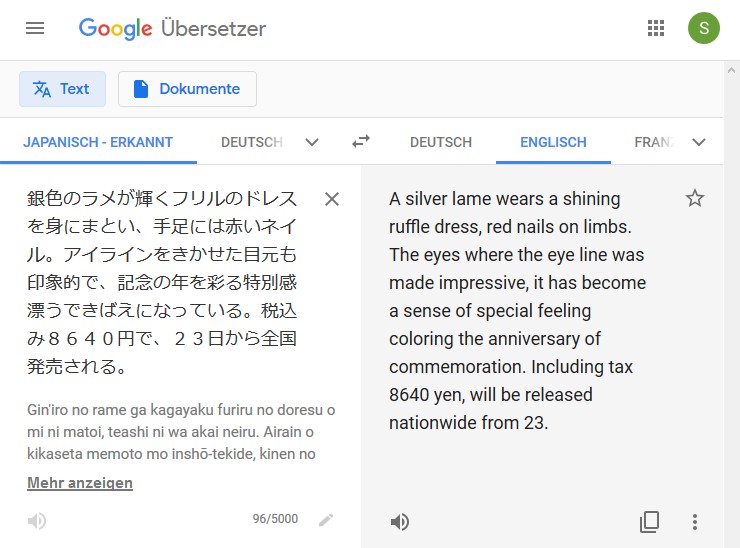

Sticking to closely related language pairs helps. If you stick German text into Google Translate or DeepL, you’ll get a good idea what the source text is about. If you take a Japanese newspaper article instead, you’ll likely receive a garbled mess.

What are you translating for?

This is a very relevant point. If all you want is to get a vague idea of what a text is about – say you receive an Italian e-mail and you want to know who’s writing to you – machine translation is great. Stick the e-mail into Google Translate and you can quickly learn that a Nigerian prince wants to wire money to your account.

If you want to translate your product description for an Italian online shop, however, machine translation will let you down. If you’re trying to sell me a product and your product description is full of mistakes, I’ll come to the conclusion that you don’t care much about quality and I’ll shop somewhere else. If your content is supposed to convey anything but the most basic meaning, if you want accuracy and creativity – like for advertising copy, for the novel you’ve written or the video game you’ve created – machine translation will fail. We’ll look at this in more detail shortly, but first…

Where machine translation succeeds

Machine translation is fast and can be comparatively cheap. Maybe not if you’re buying a fancy NMT system for your company, but certainly if you’re copy & pasting text into DeepL or Google Translate. If you need to ask where the toilet is in Xhosa or want to ask for a glass of water in Polish, machine translation is awesome.

Machine translation is also awesome if you have large volumes of text you want to make available in a different language but you don’t have the time or budget to get it done properly. Here it is obviously important to consider that your translations will likely be of low quality and you have to weigh that against not having any translation at all. As I mentioned before, if any of your text is “customer-facing”, consider what message low-quality text is going to send to those customers.

And lastly, machine translation can be useful for text that is written in a way to facilitate machine translation. In order to achieve acceptable quality, you’ll have to hire someone to post-edit your machine translations – otherwise how are you going to know where exactly the machine messed up?

If you’re thinking you could just take a really bad machine translation and hire a post-editor or proofreader to fix it cheaply, think again: Any translator worth their salt will realize your translation is beyond repair and refuse to work for a proofreading fee. Save yourself – and them – the hassle and consider the old saying: If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well.

Where machine translation fails

Machine translation has a lot of problems and can fail in a lot of areas – and the writing tips for machine translation give us some idea as to where. Machines have a hard time dealing with long sentences and anything ambiguous – that includes ambiguous words and ambiguous sentence structure. They don’t do well with humor, slogans, slang or idioms. They might also translate your product names when you don’t want them to.

More importantly, though, anything that requires cultural knowledge will be a hard task for a machine. Where would you use the formal address, where informal? What is the implicit meaning of text? (“Nice store you have there. It would be a shame if something happened to it.”) A machine won’t know. It also won’t flag potential issues in the target language or culture. Some cultures will think it patronizing if your manual uses “please” and “thank you”; well, tough luck, because if it says “please” and “thank you” in the source, your machine can’t know it’s not supposed to be there in the target.

Furthermore, machines can’t really do transcreation. Let’s assume you want a newspaper headline translated, like the one about protecting fish and hens from an otter, titled OTTER DEVASTATION. A machine will translate the words for you, but the translated headline will likely make readers scratch their heads. What you need is someone to recreate the headline for you so that it will be amusing in the target language as well. That’s a human translator’s job.

A machine won’t get puns, it won’t get sarcasm and it certainly won’t be creative. Human translators will recognize jokes in the source text, and if they can’t reproduce those in the target text, they might forgo them and maybe insert a joke in another place instead. Machines don’t do that. Machines will get confused if you suddenly verb a noun (hehe). If your dog is a mix of schnauzer and poodle, a machine will likely still not know how to translate the word Schnoodle.

It’s also worth considering that machine translation won’t recognize mistakes in the source text. This covers spelling errors as well as any logical errors. One of the things they teach you at translator school is to lose your respect for the source material. I’m exaggerating of course, but it’s very common to come across things that don’t quite make sense in the source, only to find that that’s simply because they are wrong. A translator will flag these issues to you; they will tell you if you’ve referred to the “button on the right” when it is really on the left (assuming they have a way of looking up where the button is). A machine will simply trust you when you say the button is on the right.

In his 2009 thesis for a Master in Information Technology and Cognition titled The Limits of Machine Translation, Mathias Winther Madsen looked at the failures of machine translation in detail. Granted, his thesis is now a decade old, but the problems are the same. In it he argues that “linguistic distinctions owe their significance to distinctions in practical life. […] In order to grasp meaning, a machine translation system would thus have to grasp life.”

His thesis also takes a closer look at the history of machine translation and people’s conviction in the 1950s that perfect machine translation was just a few years away. He eventually concludes: “The fact that we always seem to have come three quarters of the way again and again incites the hope that this time, we might be able to cover that last quarter. But instead of inciting hope, this situation should perhaps rather remind us of the fact that drinking a fourth beer always seems like a better idea after the first three.”

Conclusion

Machine translation has been only a few years away from being perfect since the 1950s, but it’s just not there yet. It certainly has its uses – and is being used a lot – but for translations that have to convey more than a general idea of what a text is about, it simply won’t do.

So while text that doesn’t require good quality and text that was written in a way that facilitates translation can certainly benefit from machine translations, anything requiring good quality still needs to be done by (or fixed by) actual human translators. I’ve worked with machine translation tools in the past and generally found it much easier to delete all their output and start from scratch. The subject-matter experts Microsoft is not competing with (or has not reached parity with) are exactly the people you want to hire. (On that topic: Maybe it doesn’t seem like video games are a subject matter you’d really need an expert in, but I can’t count the times I’ve seen people translate “roguelike” as “like a rogue”, thereby rendering the target text unintelligible.)

At any rate, it’s a bit sad in the grand scheme of things that technology is failing in a field where it would be so useful – but it’s certainly good for me. It appears I don’t have to go out and study anything “useful”. As it turns out, human translators are still a needed resource, and likely will be for years to come.

If you want a bonafide human to localize your video game, contact me to talk about my video game translation services and let me send you a free quote for your game! If you like, you can also sign up to my newsletter to never miss another one of my posts.

[…] CAT tool is a nifty program that helps translators be more efficient. We’re not talking about machine translation (MT) or neural machine translation (NMT) here, that’s a different matter altogether. CAT tools are […]

[…] thing is, its accuracy really depends on the text and languages you’re translating into. It can produce good results for […]